The caring and sharing feeding ecology of the Crested Shrike-tit

If a bird relies on the strengths of cooperative breeding but also lives a highly mobile life in the treetops, how can the family stay together and avoid competing with each other for scarce food resources?

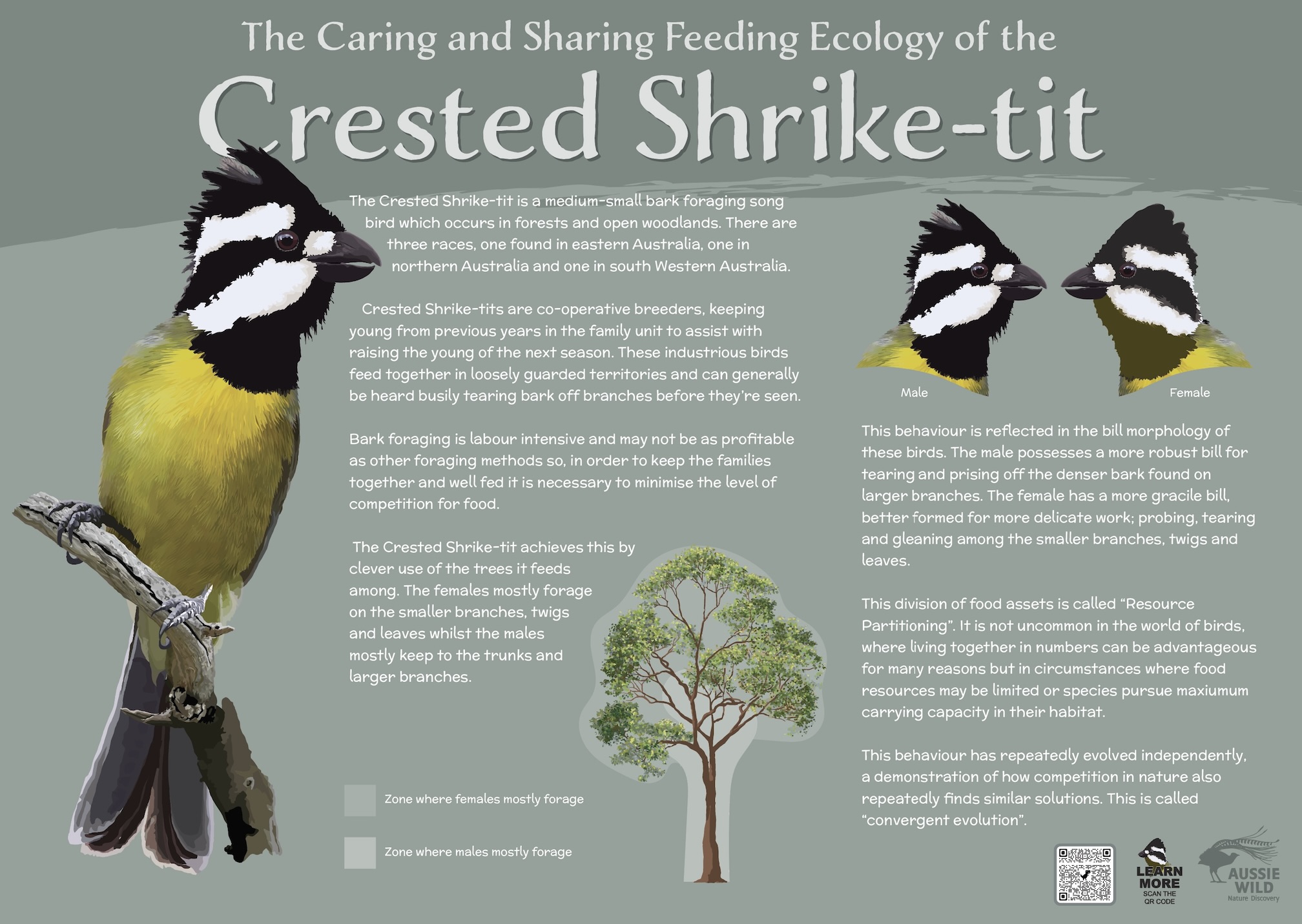

The Crested Shrike-tit is a fascinating bird. With its jaunty crest, black and white facial banding, bright yellow breast and engaging calls and behaviour, it is one of the most sought after birds on any field trip. It’s generally recognised that there are three races of shrike-tit, the Northern Crested Shrike-tit, found in the top of the Northern Territory and western Kimberley, the Eastern Crested Shrike-tit, found in south eastern Australia and the Western Crested Shrike-tit, found in the bottom corner of Western Australia.

Shrike-tits generally come to one’s attention by the sound of the males ripping at bark on the trunks of trees though sometimes their “peeeer-peeeer-peeeer” call may alert one to their presence. They appear to hold fairly large territories and are highly mobile within them. I have observed one male bird fly more than 400 metres, from one escarpment over a valley to high up a ridge on the other side of the valley.

Like many Australian birds, the shrike-tits practice cooperative breeding. This is a system where the young (usually males) of the previous season remain for the subsequent season (sometimes two) to assist with the raising of the next generation. Its widespread adoption across Australian avifauna suggests that it is a very successful way to ensure brood survival and in some instances resolve dispersal/territorial/resources issues and also ensure birds have reached a level of maturity where they can fend for themselves and breed successfully.

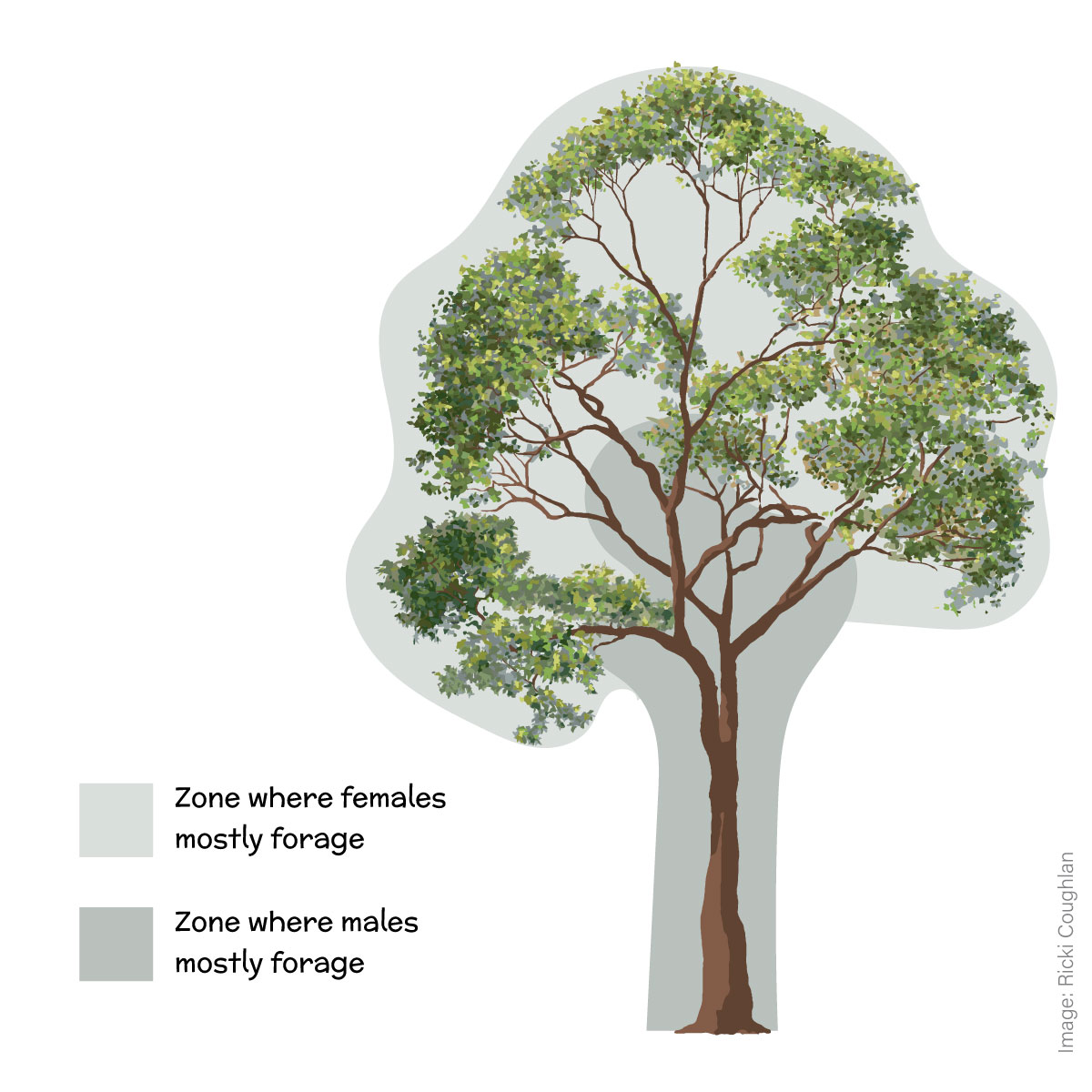

This behaviour comes at a cost. It means offspring may compete for food resources with the adults, perhaps negating the value of resource partitioning. This seems not to be the case with most species which practice this, but among dedicated bark foragers, like the shrike-tits, most treecreepers and the Varied Sittella this may be an issue. Perhaps bark foraging isn’t as profitable as other foraging practices or perhaps it’s the mobile nature of these birds over fairly large territories placing demands on them remaining as a more cohesive family unit, but the degree to which these birds practice cooperative breeding seems to correlate to the degree which they practice another behaviour: resource partitioning.

A female Crested Shrike-tit which I’ve just banded in the south-west of Sydney. Though less robust than the male’s bill, it is still beautifully designed for ripping bark off trees and the fingernails of unwary bird banders too!

Resource partitioning is generally practiced among close-knit communities of organisms which seek similar prey. I will cover this concept in relation to shorebird communities in a future post. However, we see it in forest settings among thornbills and gerygones and fairy-wrens. Species in these groups (the acanthizids and malurids) have all formed specific morphologies and behaviour which assist them in specialising in hunting and taking specific prey species (which I’ll also cover in a future post). Resource partitioning is not only widespread among birds, it is also very common in marine fish communities where vast numbers live alongside each other.

Resource partitioning may not be limited to the species level. There are many instances where the males and females of a single species may also practice resource partitioning. This may be due to taking advantage of certain prey types or substrates to serve slightly differing needs or it may be a way of ensuring greater numbers/success of a species or, in the case of cooperative breeders like the Crested Shrike-tit, ensure that a larger family group can remain as a cohesive group and not compete with each other for precious resources.

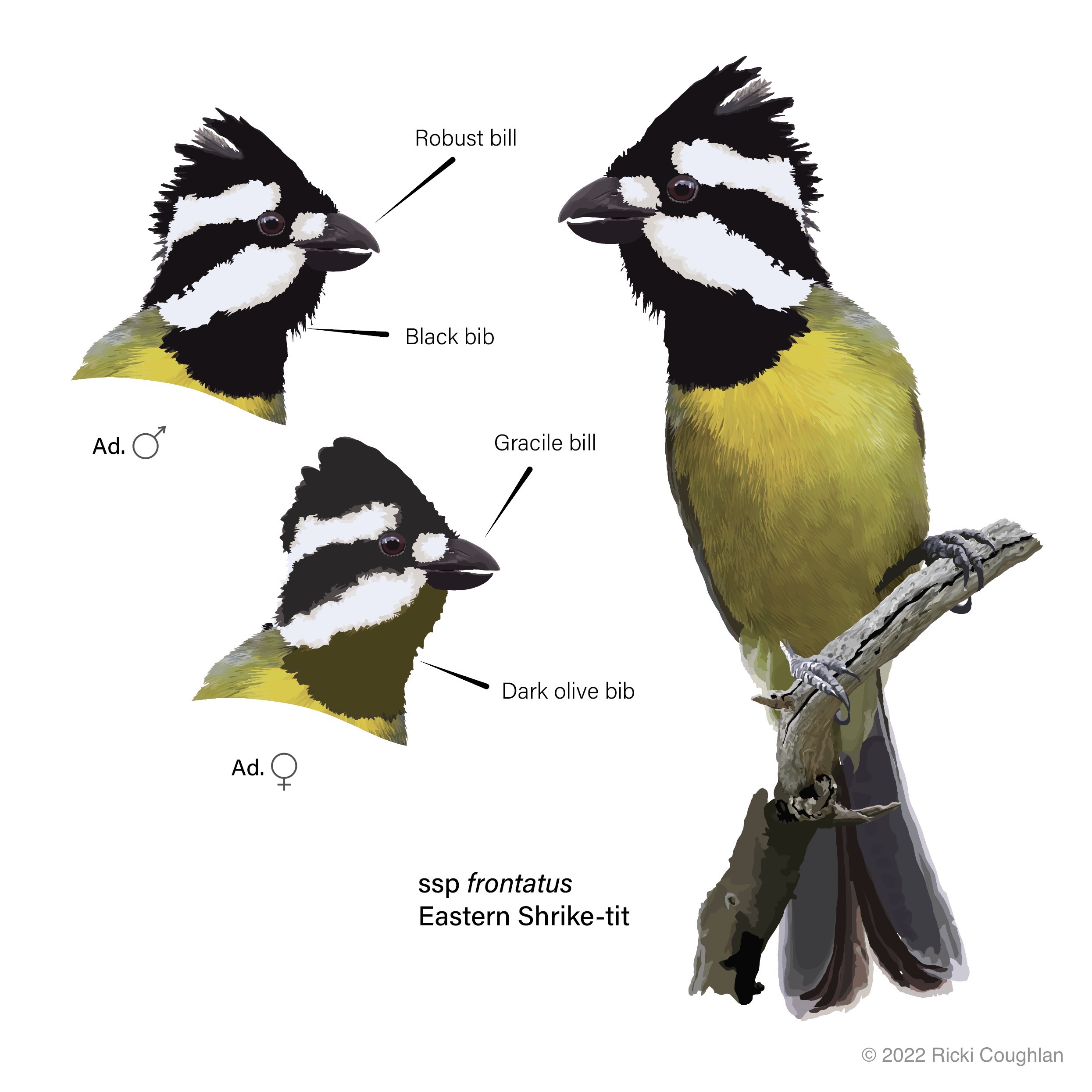

Crested Shrike-tits practice resource partitioning by males remaining on the trunks and larger boughs of the trees where they strip bark to feed on invertebrates beneath it, rip away wood on dead branches and tear at and investigate crevices to locate prey. The female shrike-tits mostly confine themselves to smaller branches and twigs and even foliage where they seek their prey. As they forage in different parts of a tree, these birds also take somewhat different prey. In this way there is enough food resources to go around a larger number of birds in a more discrete location in any given foraging sortie (ie. a single or perhaps two or three neighbouring trees).

This behaviour is reflected in the bill morphology of these birds, with the males possessing more robust bills and the females possessing the more gracile bills. This image of the male (left) and female (right) come from specimens in the Australian Museum, both collected on the northern beaches of Sydney in the 1930’s.

This “caring and sharing” behaviour has repeatedly evolved in the world of nature, reflecting its success as a tactic within a species but is of course a major driver of speciation, contributing to the patterns of diversity and abundance of life on earth.

You can celebrate this amazing story with a wall poster of this beautiful bird, available in various sizes and corflute or poster style in my shop.